What is bash?

Bash is an interactive shell:

You type in commands.

Bash executes them.

Unix users spend a lot of time manipulating files at the shell.

As a shell, it is directly available via the terminal in both Mac OS X (Applications > Utilities) and Linux/Unix.

At the same time, bash is also a scripting language:

Bash scripts can automate routine or otherwise arduous tasks involved in systems administration.

Why use bash?

Here are example tasks for which you might use bash:

- Orchestrating system start-up/shutdown tasks.

- Automatically renaming a collection of files.

- Finding all duplicate mp3s on a hard drive.

- Orchestrating a suite of tools for cracking a password database.

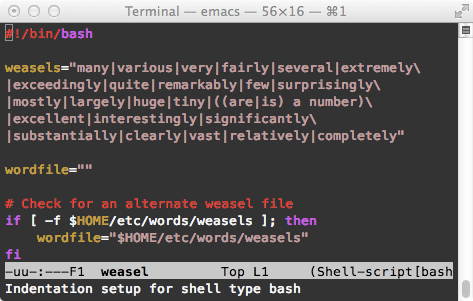

- Finding weasel words in your writing.

- Implementing a relational database out of text files.

- Simplifying configuration and reconfiguration of software.

Bash as a scripting language

To create a bash script, you place #!/bin/bash

at the top of the file.

Then, change the permissions on the file to make it executable:

$ chmod u+x scriptname

To execute the script from the current directory, you can run

./scriptname and pass any parameters you wish.

When the shell executes a script, it finds the

#!/path/to/interpreter.

It then runs the interpreter (in this case,

/bin/bash) on the file itself.

The #! convention is why so many scripting languages

use # for comments.

Here's an example bash script that prints out the first argument:

#!/bin/bash # Use $1 to get the first argument: echo $1

Comments

Comments in bash begin with # and run to the end of the line:

echo Hello, World. # prints out "Hello, World."

Variables/Arrays

Variables in bash have a dual nature as both arrays and variables.

To set a variable, use =:

foo=3 # sets foo to 3

But, be sure to avoid using spaces:

foo = 3 # error: invokes command `foo' with arguments `=' and `3'

If you want to use a space, you can dip into the

expression sub-language that exists inside ((

and )):

(( foo = 3 )) # Sets foo to 3.

To reference the value of a variable, use a dollar sign, $:

echo $foo ; # prints the value of foo to stdout

You can delete a variable with unset:

foo=42 echo $foo # prints 42 unset foo echo $foo # prints nothing

Of course, you can assign one variable to another:

foo=$bar # assigns the value of $bar to foo.

If you want to assign a value which contains spaces, be sure to quote it:

# wrong: foo=x y z # sets foo to x; will try to execute y on z # right: foo="x y z" # sets foo to "x y z"

It is sometimes necessary to wrap a reference to a variable is braces:

echo ${foo} # prints $foo

This notation is necessary for variable operations and arrays.

There is no need to declare a variable as an array: every variable is an array.

You can start using any variable as an array:

foo[0]="first" # sets the first element to "first" foo[1]="second" # sets the second element to "second"

To reference an index, use the braces notation:

foo[0]="one"

foo[1]="two"

echo ${foo[1]} # prints "two"

When you reference a variable, it is an implicit reference to the first index:

foo[0]="one" foo[1]="two" echo $foo # prints "one"

You can also use parentheses to create an array:

foo=("a a a" "b b b" "c c c")

echo ${foo[2]} # prints "c c c"

echo $foo # prints "a a a"

To access all of the values in an array, use the special subscript

@ or *:

array=(a b c)

echo $array # prints a

echo ${array[@]} # prints a b c

echo ${array[*]} # prints a b c

To copy an array, use subscript @, surround it with quotes,

and surround that with parentheses:

foo=(a b c)

bar=("${foo[@]}")

echo ${bar[1]} # prints b

Do not try to copy with just the variable:

foo=(a b c)

bar=$foo

echo ${bar[1]} # prints nothing

And, do not forget the quotes, or else arrays with space-containing elements will be screwed up:

foo=("a 1" "b 2" "c 3")

bar=(${foo[@]})

baz=("${foo[@]}")

echo ${bar[1]} # oops, print "1"

echo ${baz[1]} # prints "b 2"

Special variables

There are special bash variables for grabbing arguments to scripts and functions:

echo $0 # prints the script name

echo $1 # prints the first argument

echo $2 # prints the second argument

echo $9 # prints the ninth argument

echo $10 # prints the first argument, followed by 0

echo ${10} # prints the tenth argument

echo $# # prints the number of arguments

The variable $? holds the "exit status"

of the previously executed process.

An exit status of 0 indicates the process "succeeded" without error.

An exit status other than 0 indicates an error.

In shell programming, true is a program that

always "succeeds," and false is a program that always "fails":

true echo $? # prints 0 false echo $? # will never print 0; usually prints 1

The process id of the current shell is available as $$

The process id of the most recently backgrounded process is

available as $!:

# sort two files in parallel: sort words > sorted-words & # launch background process p1=$! sort -n numbers > sorted-numbers & # launch background process p2=$! wait $p1 wait $p2 echo Both files have been sorted.

Operations on variables

In a feature unique among many languages, bash can operate on the value of a variable while dereferencing that variable.

String replacement

Bash can replace a string with another string:

foo="I'm a cat."

echo ${foo/cat/dog} # prints "I'm a dog."

To replace all instances of a string, use double slashes:

foo="I'm a cat, and she's cat."

echo ${foo/cat/dog} # prints "I'm a dog, and she's a cat."

echo ${foo//cat/dog} # prints "I'm a dog, and she's a dog."

These operations generally do not modify the variable:

foo="hello"

echo ${foo/hello/goodbye} # prints "goodbye"

echo $foo # still prints "hello"

Without a replacement, it deletes:

foo="I like meatballs."

echo ${foo/balls} # prints I like meat.

The ${name#pattern} operation

removes the shortest prefix of ${name}

matching pattern,

while ## removes the longest:

minipath="/usr/bin:/bin:/sbin"

echo ${minipath#/usr} # prints /bin:/bin:/sbin

echo ${minipath#*/bin} # prints :/bin:/sbin

echo ${minipath##*/bin} # prints :/sbin

The operator % is the same, except for suffixes instead of

prefixes:

minipath="/usr/bin:/bin:/sbin"

echo ${minipath%/usr*} # prints nothing

echo ${minipath%/bin*} # prints /usr/bin:

echo ${minipath%%/bin*} # prints /usr

String/array manipulation

Bash has operators that operate on both arrays and strings.

For instance, the prefix operator # counts the number of

characters in a string or the number of elements in an array.

It is a common mistake to accidentally operate on the first element of an array as a string, when the intent was to operate on the array.

Even the Bash Guide for Beginners contains a misleading example:

ARRAY=(one two three)

echo ${#ARRAY} # prints 3 -- the length of the array?

However, if we modify the example slightly, it seems to break:

ARRAY=(a b c)

echo ${#ARRAY} # prints 1

This is because ${#ARRAY} is the same as ${#ARRAY[0]},

which counts the number of characters in the first element, a.

It is possible to count the number of elements in the array,

but the array must be specified explicitly with @:

ARRAY=(a b c)

echo ${#ARRAY[@]} # prints 3

It is also possible to slice strings and arrays:

string="I'm a fan of dogs."

echo ${string:6:3} # prints fan

array=(a b c d e f g h i j)

echo ${array[@]:3:2} # prints d e

Existence testing

Some operations test whether the variable is set:

unset username

echo ${username-default} # prints default

username=admin

echo ${username-default} # prints admin

For operations that test whether a variable is set,

they can be forced to check whether the variable is set and

not empty by adding a colon (":"):

unset foo

unset bar

echo ${foo-abc} # prints abc

echo ${bar:-xyz} # prints xyz

foo=""

bar=""

echo ${foo-123} # prints nothing

echo ${bar:-456} # prints 456

The operator = (or :=) is like the operator -, except

that it also sets the variable if it had no value:

unset cache

echo ${cache:=1024} # prints 1024

echo $cache # prints 1024

echo ${cache:=2048} # prints 1024

echo $cache # prints 1024

The + operator yields its value if the

variable is set, and nothing otherwise:

unset foo

unset bar

foo=30

echo ${foo+42} # prints 42

echo ${bar+1701} # prints nothing

The operator ? crashes the program with the specified message

if the variable is not set:

: ${1?failure: no arguments} # crashes the program if no first argument

(The : command ignores all of its arguments, and is equivalent to true.)

Indirect look-up

Bash allows indirect variable/array look-up

with the ! prefix operator.

That is, ${!expr} behaves like

${${expr}}, if only that worked:

foo=bar

bar=42

echo ${!foo} # prints $bar, which is 42

alpha=(a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z)

char=alpha[12]

echo ${!char} # prints ${alpha[12]}, which is m

Array quirks: * versus @

There are two additional special variables: $* and $@.

[All of the behaviors described in this section apply to arrays when accesed via

${array[*]} or ${array[@]} as well.]

The both seem to contain the arguments passed to the current script/procedure, but they have subtly different behavior when quoted:

To illustrate the difference, we need to create a couple helper scripts.

First, create print12:

#!/bin/bash # prints the first parameter, then the second: echo "first: $1" echo "second: $2"

Then, create showargs:

#!/bin/bash echo $* echo $@ echo "$*" echo "$@" bash print12 "$*" bash print12 "$@"

Now, run showargs:

$ bash showargs 0 " 1 2 3"

to print:

0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 first: 0 1 2 3 second: first: 0 second: 1 2 3

This happens because "$*" combines all arguments into a single

string, while "$@" requotes the individual arguments.

There is another subtle difference between the two:

if the variable IFS (internal field separator) is set,

then the contents of this variable are spliced between

elements in "$*".

Create a script called atvstar:

#!/bin/bash IFS="," echo $* echo $@ echo "$*" echo "$@"

And run it:

$ bash atvstar 1 2 3

to print:

1 2 3 1 2 3 1,2,3 1 2 3

IFS must contain a single character.

Again, these same quoting behaviors transfer to

arrays when subscripted with * or @:

arr=("a b" " c d e")

echo ${arr[*]} # prints a b c d e

echo ${arr[@]} # prints a b c d e

echo "${arr[*]}" # prints a b c d e

echo "${arr[@]}" # prints a b c d e

bash print12 "${arr[*]}"

# prints:

# first: a b c d e

# second:

bash print12 "${arr[@]}"

# prints:

# first: a b

# second: c d e

Strings and quoting

Strings in bash are sequences of characters.

To create a literal string, use single quotes; to create an interpolated string, use double quotes:

world=Earth foo='Hello, $world!' bar="Hello, $world!" echo $foo # prints Hello, $world! echo $bar # prints Hello, Earth!

In intepolated strings, variables are converted to their values.

Scope

In bash, variable scope is at the level of processes: each process has its own copy of all variables.

In addition, variables must be marked for export to child processes:

foo=42 bash somescript # somescript cannot see foo export foo bash somescript # somescript can see foo echo "foo = " $foo # always prints foo = 42

Let's suppose that this is somescript:

#!/bin/bash echo "old foo = $foo" foo=300 echo "new foo = $foo"

The output from the code would be:

old foo = new foo = 300 old foo = 42 new foo = 300 foo = 42

Expressions and arithmetic

It is possible to write arithmetic expressions in bash, but with some caution.

The command expr prints the result of arithmetic expressions,

but one must take caution:

expr 3 + 12 # prints 15 expr 3 * 12 # (probably) crashes: * expands to all files expr 3 \* 12 # prints 36The

(( assignable = expression )) assignment notation

is more forgiving:

(( x = 3 + 12 )); echo $x # prints 15 (( x = 3 * 12 )); echo $x # prints 36

If you want the result of an arithmetic expression without assigning it,

you can use $((expression)):

echo $(( 3 + 12 )) # prints 15 echo $(( 3 * 12 )) # prints 36

While declaring variables implicitly is the norm in bash, it is possible to declare variables explicitly and attach a type to them.

The form declare -i variable creates an explicit integer variable:

declare -i number number=2+4*10 echo $number # prints 42 another=2+4*10 echo $another # prints 2+4*10 number="foobar" echo $number # prints 0

Assignments to integer variables will force evaluation of expressions.

Files and redirection

Every process in Unix has access to three input/output channels by default: STDIN (standard input), STDOUT (standard output) and STDERR (standard error).

When writing to STDOUT, the output appears (by default) at the console.

When reading from STDIN, it reads (by default) directly from what the user types into the console.

When writing to STDERR, the output appears (by default) at the console.

All of these channels can be redirected.

For instance, to dump the contents of a file into STDIN (instead of accepting user input), use the < operator:

# prints out lines in myfile containing the word foo: grep foo < myfile

To dump the output of a command into a file, use the > operator:

# concatenates file1 with file2 in new file combined: cat file1 file2 > combined

To append to the end of a file, use the >> operator:

# writes the current date and time to the end of a file named log: date >> log

To specify the contents of STDIN literally, in a script, use the <<endmarker notation:

cat <<UNTILHERE All of this will be printed out. Since all of this is going into cat on STDIN. UNTILHERE

Everything until the next instance of endmarker by itself on a line is redirected to STDIN.

To redirect error output (STDERR), use the operator 2>:

# writes errors from web daemon start-up to an error log: httpd 2> error.log

In fact, all I/O channels are numbered, and > is the same as 1>.

STDIN is channel 0, STDOUT is channel 1, while STDERR is channel 2.

The notation M>&N redirects the output of

channel M to channel N.

So, it's straightforward to have errors display on STDOUT:

grep foo nofile 2>&1 # errors will appear on STDOUT

Capturing STDOUT with backquotes

There is another quoting form in bash that looks like a string--backtick: ``.

These quotes execute the commands inside of them and drop the output of the process in place:

# writes the date and the user to the log: echo `date` `whoami` >> log

Given that is sometimes useful to nest these expansions, newer shells have added

a nestable notation: $(command):

# writes the date and the user to the log: echo $(date) $(whoami) >> log

It is tempting to import the contents of a file with `cat

path-to-file`, but there is a simpler built-in shorthand:

`<path-to-file`:

echo user: `<config/USER` # prints the contents of config/USER

Redirecting with exec

The special bash command exec can manipulate

channels over ranges of commands:

exec < file # STDIN has become file exec > file # STDOUT has become file

You may wish to save STDIN and STDOUT to restore them later:

exec 7<&0 # saved STDIN as channel 7 exec 6>&1 # saved STDOUT as channel 6

If you want to log all output from a segment of a script, you can combine these together:

exec 6>&1 # saved STDOUT as channel 6 exec > LOGFILE # all further output goes to LOGFILE # put commands here exec 1>&6 # restores STDOUT; output to console again

Pipes

It is also possible to route the STDOUT of one process into the STDIN of another

using the | (pipe) operator:

# prints out root's entry in the user password database: cat /etc/passwd | grep root

The general form of the pipe operator is:

outputing-command | inputing-command

And, it is possible to chain together commands in "pipelines":

# A one-liner to find space hogs in the current directory:

# du -cks * # prints out the space usage

# of files in the current directory

# sort -rn # sorts STDIN, numerically,

# by the first column in reverse order

# head # prints the first 10 entries from STDIN

du -cks * | sort -rn | head

Some program accept a filename from which to read instead of reading from STDIN.

For these programs, or programs which accept multiple filenames, there is a

way to create a temporary file that contains the output of a command,

the <(command) form.

The expression <(command) expands into the name of a temporary file

that contains the output of running command.

This is called process substitution.

# appends uptime, date and last line of event.log onto main.log: cat <(uptime) <(date) <(tail -1 event.log) >> main.log

Processes

Bash excels at coordinating processes.

Pipelines act to coordinate several processes together.

It is also possible to run processes in parallel.

To execute a command in the background, use the &

postfix operator:

time-consuming-command &

And, to fetch the process id, use the $! special variable

directly after spawning the process:

time-consuming-command & pid=$!

The wait command waits for a process id's associated process

to finish:

time-consuming-command & pid=$! wait $pid echo Process $pid finished.

Without a process id, wait waits for all child

processes to finish.

To convert a folder of images from JPG to PNG in parallel:

for f in *.jpg

do

convert $f ${f%.jpg}.png &

done

wait

echo All images have been converted.

Globs and patterns

Bash provides uses the glob notation to match on strings and filenames.

In most contexts in bash, a glob pattern automatically expands to an array of all matching filenames:

echo *.txt # prints names of all text files

echo *.{jpg,jpeg} # prints names of all JPEG files

Glob patterns have several special forms:

*matches any string.?matches a single character.[chars]matches any character inchars.[a-b]matches any character betweenaandb.

Using these patterns,

it's easy to remove all files of the form fileNNN, where NNN is some 3-digit number:

rm file[0-9][0-9][0-9]

The curly brace "set" form seems to act like a pattern, but it will expand even if the files do not exist:

{string1,string2,...,stringN} expands to

string1 or string2 or ...

It is possible to create a "bash bomb": a pattern that grows exponentially in size under expansion:

echo {0,1} # prints 0 1

echo {0,1}{0,1} # prints 00 01 10 11

echo {0,1}{0,1}{0,1} # prints 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

Control structures

Like most languages, bash supports control structures for conditionals, iteration and subroutines.

Conditionals

If-then-else-style conditionals exist in bash, as in other languages.

However, in bash the condition is a command, and an exit status of success (0) is "true," while an exit status of fail (non-zero) is "false.":

# this will print: if true then echo printed fi # this will not print: if false then echo not printed fi

Bash can take different actions on whether a program succeeded or failed:

if httpd -k start then echo "httpd started OK" else echo "httpd failed to start" fi

In bash, many conditions are built from the special command test.

The command test takes many flags to perform conditional tests.

Run help test to list them all.

Some popular flags include:

-e fileis true iff a specific file/directory exists.-z stringis true iff the given string is empty.string1 = string2is true iff the two strings are equal.

There is an alternate notation for test args using square brackets:

[ args ].

Conditionals can check if arguments are meaningful:

if [ "$1" = "-v" ] then echo "switching to verbose output" VERBOSE=1 fi

Iteration

The while command; do commands; done form

executes commands until the test command completes with

non-zero exit status:

# automatically restart the httpd in case it crashes:

while true

do

httpd

done

It's possible to iterate over the elements in an array

with a for var in array; do commands; done loop:

# compile all the c files in a directory into binaries:

for f in *.c

do

gcc -o ${f%.c} $f

done

Subroutines

Bash subroutines are somewhat like separate scripts.

There are two syntaxes for defining a subroutine:

function name {

commands

}

and:

name () {

commands

}

Once declared, a function acts almost like a separate script:

arguments to the function come as $n for the nth

argument.

One major different is that functions can see and modify variables defined in the outer script:

count=20

function showcount {

echo $count

count=30

}

showcount # prints 20

echo $count # prints 30

Examples

Putting this all together allows us to write programs in bash.

Here is a subroutine for computing factorial:

function fact {

result=1

n=$1

while [ "$n" -ge 1 ]

do

result=$(expr $n \* $result)

n=$(expr $n - 1)

done

echo $result

}

Or, with the expression notation:

function facter {

result=1

n=$1

while (( n >= 1 ))

do

(( result = n * result ))

(( n = n - 1 ))

done

echo $result

}

Or, with declared integer variables:

factered () {

declare -i result

declare -i n

n=$1

result=1

while (( n >= 1 ))

do

result=n*result

n=n-1

done

echo $result

}

More resources

- Wooledge Bash Guide

- Advanced Bash Scripting Guide

-

Unix Power Tools

:

-

The UNIX and Linux System Administration Handbook

:

-

Classic Shell Scripting

: